Phoenixville’s Edmund Bacon Visualized and Reshaped a Modern Philadelphia

When I graduated from Collingdale High School in Delaware County in 1971, I went off to college in Milwaukee thinking I was going to be an architect.

A class in my first year dealt with how cities were purposely developed, how buildings should fit into the fabric of a city, how neighborhoods knitted with commercial and business zoning, traffic patterns, creation of people-friendly outdoor spaces, etc., to form cities.

But good architecture is only half the battle if cites don’t clearly think out and execute a plan for how to develop, and that is true of cities both at the large metropolitan level and for small urban communities.

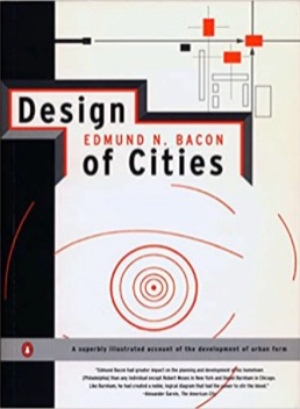

For this studio, one of my required texts was a book, “Design of Cities,” written by Edmund Bacon of Phoenixville. If that name looks or sounds familiar, the answer is yes, Edmond and his wife Ruth are the parents of actor Kevin Bacon.

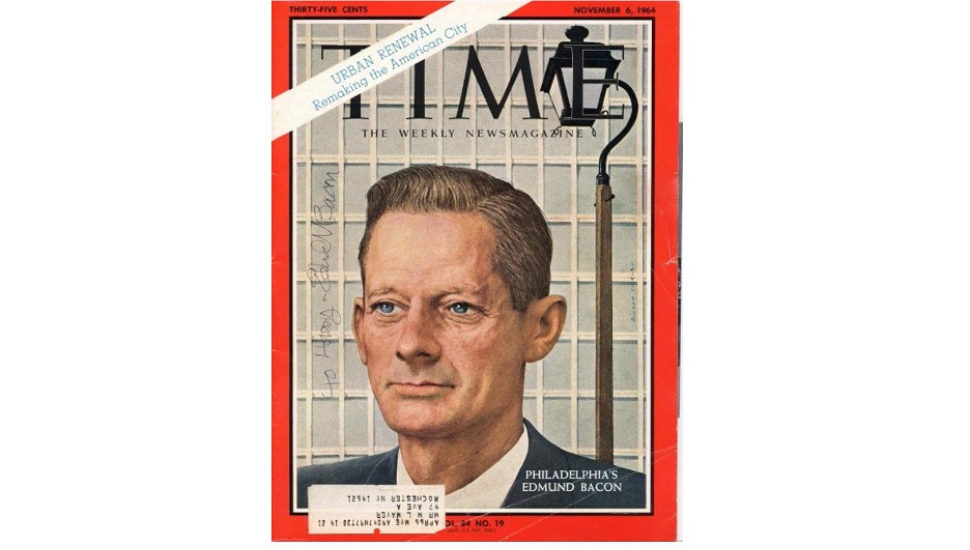

But at the time I took this class, Kevin’s star was still on the rise, and he wasn’t as well-known as his father, who had appeared on the cover of Time.

Paging through Bacon’s book that first time, I was shocked: before me, a detailed explanation and graphic illustration of how Philadelphia, whose streets I had walked in my youth, has been strategically planned and developed over the years. I had no clue! And here it all was, in this book, written almost 10 years before I went to college!

“Design of Cities” is still used today in architecture and urban planning schools around the world.

Bacon starts by reviewing the design of ancient cities, and with easily understood graphics, illustrates how cities were formally planned and developed over their centuries of existence, such as Paris, London, and more.

Here in the US, there are examples of cities that have followed those ancient principles in how they planned their growth. L’Enfant’s plan for Washington, DC, Young’s width of streets and the general layout of Salt Lake City, Utah, to name a few examples.

And if you know anything about local history, William Penn is due his kudos for the early layout of Philadelphia, the placement of City Hall, the green spaces that gave us Rittenhouse and Washington Squares, and other open green spaces, how the streets were named, etc.

Edmund Bacon, it turns out, was the Philadelphia City Planning Commissioner from 1949 to 1970 and is credited with developing the very public spaces of Penn Center, Penn’s Landing, Society Hill, The Galleria, and more. And he tied his vision into the past development that leads from City Hall, through Logan Circle and up the stairs at the end of Franklin Parkway at the Museum of Art.

One notable example of Bacon’s planned and executed changes most are familiar with: Independence Mall.

There was a time the Pennsylvania Statehouse was immediately surrounded by street-level retail and loft-type manufacturing and warehouse buildings, 3-4 story brick buildings, tightly packed together, turn-of-the-19th-to-20th century construction, right across Chestnut St from the Liberty Bell’s home (before it moved to the Pavilion across the street).

Bacon, in planning the Mall, highlighted and enhanced Independence Hall as the crown jewel of Philadelphia’s historical past, not only to the City, but to the country and the world as well.

Planning the space is only half the war: convincing the politicians and bureaucrats to approve and execute such a plan should be Bacon’s most lasting legacy. The foresight of the City Fathers to execute and maintain adherence to these visionary planning strategies cannot be overstated, either.

Other planning successes have followed Bacon’s tenure. Moving the Convention Center to a converted, re-purposed Reading Terminal, for one.

While it was not part of Bacon’s original plans, but having set the precedent, the City and the architects since in this and other developments have fitted their buildings with Bacon’s efforts clearly in mind, and have added to the fabric of a more vibrant downtown.

Bacon’s book is highly illustrated to show how planning concepts drawn from historical examples work, including zoning, managed urban growth, creating green spaces and pedestrian-friendly streetscapes. Bacon’s legacy is in the brick, stone, pavers, concrete, and open spaces left as a result of his and before him, William Penn’s efforts. While urban planning may sound boring, if you have any interest in how the lessons of ancient cities applies to modern metropolises, and specifically Philadelphia, “Design of Cities” is worth the read.

Stay Connected, Stay Informed

Subscribe for great stories in your community!

"*" indicates required fields

![ForAll_Digital-Ad_Dan_1940x300[59]](https://montco.today/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/06/ForAll_Digital-Ad_Dan_1940x30059.jpg)

![95000-1023_ACJ_BannerAd[1]](https://montco.today/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/03/95000-1023_ACJ_BannerAd1.jpg)